Darkness After Birth: Understanding Postpartum Depression

Effective treatments exist, but seeking medical help without delay is crucial.

Posted Aug 20, 2020. Psychology Today

“Once upon a time, there was a little girl who dreamed of being a mommy. She wanted, more than anything, to have a child … one day, finally, she became pregnant. She was thrilled beyond belief. She had a wonderful pregnancy and a perfect baby girl. At long last, her dream of being a mommy had come true. But instead of being relieved and happy, all she could do was cry.” This is Brooke Shields’ moving opening to her 2005 book Down Came the Rain, a frank personal account of postpartum depression. Following the example of Marie Osmond’s Behind the Smile (2001), Shields bravely went public to raise awareness of a condition that can severely afflict any new mother out of the blue.

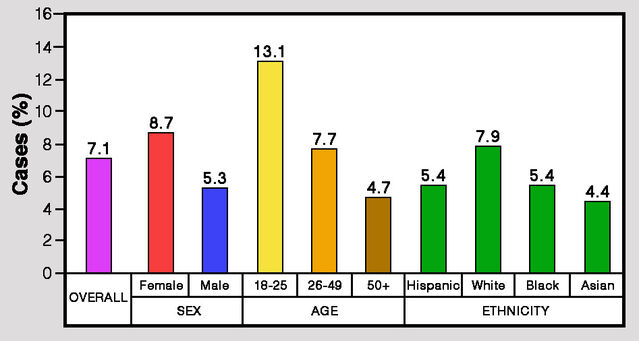

In fact, in industrialized countries one out of every seven women experiences serious depression following birth. Levels are even higher, around one in five, in economically disadvantaged nations. But needless feelings of failure, shame and guilt impede open discussion and can lead to suicide. Tell-it-all books like those of Marie Osmond and Brooke Shields have triggered increased vigilance, but this topic still deserves far more attention than it gets.

What is postpartum depression?

Effective monitoring of postpartum depression demands a suitable definition. In industrialized societies, over half of new mothers suffer diffuse “baby blues,” usually lasting a fortnight at most. But postpartum depression, first medically recognized in the 1850s, is a more persistent, debilitating condition. Symptoms typically appear quite soon after birth, commonly within the first month, although they may emerge several months later. Added to tiredness and insomnia, which are not unexpected, specific symptoms include inexplicable sadness, anxiety, irritability, weeping bouts, social withdrawal and disturbance of appetite. In really severe cases — thankfully only one woman in 500 — full-blown postpartum psychosis develops.

Systematic screening of postpartum depression has become established over the past 30 years. In 1987, John Cox and colleagues proposed a now widely used key recognition tool, the Edinburgh Post-Natal Depression Scale (EPDS), which a new mother can complete herself in just five minutes. Responses are needed for 10 statements, each having four alternative options ranging from definitely negative to definitely positive: (1) the capacity to appreciate humour; (2) anticipation of enjoyment; (3) unnecessary self-blame; (4) unaccountable anxiety; (5) groundless fear or panic; (6) feeling overwhelmed by things; (7) insomnia; (8) pervasive sadness; (9) weeping from unhappiness; (10) thoughts of self-harm. Zero to three points are awarded for each response, yielding a maximum score of 30. A total of 13 or more indicates that professional evaluation is needed.

Risk factors for postpartum depression

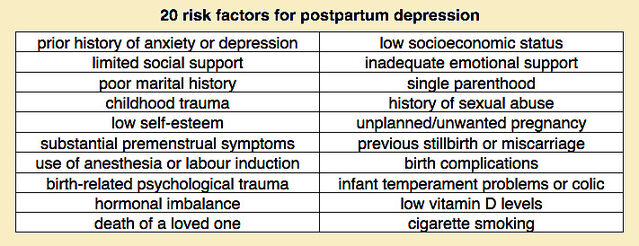

Countless studies have linked postpartum depression to many different conditions, often in combination. Twenty potential factors, typically reflecting stressful life events, are listed in this table:

In Brooke Shields’ case, factors in that list included a family history of depression, the recent death of her father, a prior miscarriage, the challenges of in vitro fertilization, and trauma in childbirth. Moreover, she experienced the stress of moving to a new home. In addition, she encountered initial problems with breastfeeding, which are of concern because bottle-feeding is another prominent factor associated with postpartum depression.

article continues after advertisement

Numerous studies have reported links between postpartum depression and bottle-feeding. A 1998 paper by Mohammed Abou-Saleh and colleagues is of special interest because of its focus on hormonal aspects. A key finding from examining blood levels of six hormones in 70 new mothers a week after birth was that those diagnosed with ongoing postpartum depression (using EPDS) had significantly lower prolactin levels. Strikingly, mothers who bottle-fed their infants rather than breastfeeding also had lower prolactin levels.

Subsequently, in 2006, a paper by Sarah Breese McCoy and colleagues (again using EPDS) compared women assessed four weeks after birth, 81 flagged for postpartum depression and 128 not. Three out of six risk factors examined showed significant associations. The strongest was found with bottle-feeding, with a risk of depression more than twice as high as for breastfeeding mothers. Other associations emerged for prior depression (risk increased almost 90%) and smoking (risk increased almost 60%). Although the risk of postpartum depression was somewhat greater in women following births by Caesarean section, the difference was not statistically significant. A very recent paper by Hsiao-Chen Chiu and colleagues examined the risk of postpartum depression in relation to early breastfeeding in 333 pregnant women. Higher EPDS scores were significantly associated with a decreased (approximately halved) likelihood of breastfeeding. In this case, other significant factors included C-section, with which the risk of postnatal depression was almost tripled.

Of course, the oft-reported link between bottle-feeding and postpartum depression can be explained in (at least) two ways. It might indicate that breastfeeding lowers the incidence of postpartum depression, but it could be that depressed women are less likely to breastfeed. In a 1997 paper, Shaila Misri and colleagues used questionnaire data to explore this relationship in 51 postpartum women suffering from depression who had stopped breastfeeding. Most of them (83%) reported that their depression began before they stopped breast-feeding. Moreover, whether or not breast-feeding persisted was seemingly unrelated to the severity of depression. These findings suggest that postnatal depression is the cause, rather than the outcome, of reduced breastfeeding.

Treatment of postpartum depression

The standard medical approach to treating pregnancy-related depression is much the same as for any other major form of depression, eloquently described by Lewis Wolpert as “malignant sadness.” It is generally accepted that women are more likely to be diagnosed with major depression than men. Current leading treatments are psychotherapy, medication with antidepressants, hormonal therapy and participation in a support group, possibly in combination.

article continues after advertisementMany different factors have been implicated in postpartum depression and other pregnancy-related woes. For certain aspects, such as bottle-feeding rather than breastfeeding, a consistent connection has been identified. For other factors, notably C-sections, the jury is still out. Such multifactorial complexity and a paucity of information from animal models have hindered successful treatment.

Sources often state that postpartum depression is caused by pronounced hormonal changes around the time of birth. In women, estrogens and progesterone rise continuously during pregnancy to reach very high levels, fall precipitously around the time of birth and may fluctuate considerably thereafter. Some evidence indicates that maternal feelings and effectiveness may be linked to hormone levels, notably for estrogens, progesterone and prolactin. These hormones or surrogates thereof have been used in various ways, with some success, to treat postpartum depression. However, it is clear that hormones are certainly not the sole factor.

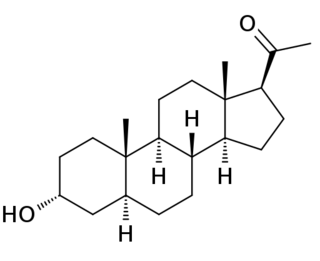

Recently, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been widely used to treat postnatal depression. However, a 2019 review by Ariela Frieder and colleagues reported positive results from trials of intravenously injected brexanolone — a synthetic form of allopregnanolone (a naturally occurring steroid that acts on the brain). Trials indicated that brexanolone quickly reduces symptoms of postpartum depression, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved its use for treatment in 2019.

article continues after advertisementOverall, the good news is that treating postpartum depression with a combination of therapy and medication is often very effective. It generally takes a while, but patients do usually recover in due course. The crucial point is that any woman feeling depressed beyond two weeks after birth should seek medical advice and not try to fight the battle alone.

Additional considerations

Postpartum depression is a complex condition with multiple causes that perhaps unleash a basic disorder with both biological and psychological components. It has many effects that defy comprehensive coverage. However, some special points do deserve mention. Perhaps the most important is that — if left untreated — depression in a new mother (and presumably in a new father as well) can have a significant impact on infant and child development.

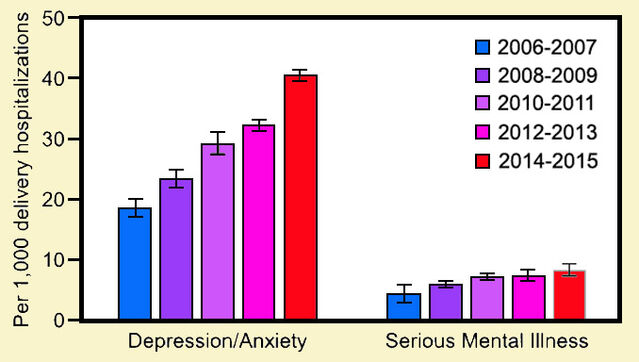

A worrying finding recently reported by Kimberly McKee and colleagues is that the incidence of postpartum anxiety and depression in the USA more than doubled over the decade between 2006 and 2015. In tandem, the incidence of serious mental illness also steadily increased. This underscores the need for more research and increased monitoring during pregnancy and after childbirth.

References

Abou-Saleh, M.T., Ghubash, R., Karim, L., Krymski, M. & Bhai, I. (1998) Hormonal aspects of postpartum depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 23:465-475.

Anonymous (2009) Postpartum disorder. Diagnosis Dictionary, Psychology Today

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/conditions/postpartum-disorder

Chiu, H.-C., Wang, H.-Y., Hsiao, J.-C., Tzeng, I-S., Yiang, G.-T., Wu, M.-Y. & Chang, Y.-K. (2020) Early breastfeeding is associated with low risk of postpartum depression in Taiwanese women. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 40:160-166.